In Allen Kopp’s new short story, Late of Cherry Street, we learn that sometimes one just needs to learn where they are going. Do read.

By: Allen Kopp

Allen Kopp lives in St. Louis, Missouri, USA. His fiction has appeared in Short Story America, A Twist of Noir, Midwest Literary Magazine, Abandoned Towers Magazine, Danse Macabre, Short-Story.Me, Foliate Oak Literary Journal, Berg Gasse 19, Santa Fe Writers’ Project Journal, Copperfield Review, Superstition Review, Midwestern Gothic Literary Magazine, Skive Magazine, ISFN Anthology #1, Best Genre Short Stories Anthology #1, Wilde Oats, Writers’ Stories, Yesteryear Fiction, Diverse Voices Quarterly, Deadman’s Tome, Necrology Shorts, Bewildering Stories, State of Imagination, Death Head Grin, Corner Club Press, Pulse Literary Magazine, Poor Mojo’s Almanac(k), The Legendary, The Fringe Magazine, and many others.

Click here for a PDF of Late of Cherry Street.

Late of Cherry Street

By: Allen Kopp

Cora Sue Hightower developed a summer cold, which turned into pneumonia and then into something worse. She was supposed to get better but she didn’t. She faded very fast and died in her own bed on a lovely afternoon in late June with her mother, father, and younger sister at her side. She was only eighteen years old.

Ashenbrenner and Sons came in their shiny black hearse within minutes of being called and took Cora Sue away underneath a blanket on a stretcher. They worked over her body for a day and a half in their basement laboratory, drawing the blood out of her body and replacing it with embalming fluid. They called in a hairdresser and a makeup artist to work their magic and dressed her according to her mother’s explicit instructions. In short, they did all they could to make sure she would look in death exactly as she had looked in life.

Almost everybody who had ever known Cora Sue in her life came for the visitation and viewing: friends past and present, school teachers, acquaintances of her parents who saw her maybe one time when she was five years old, a slew of third and fourth cousins from out of town, and on and on. So many people showed up, in fact, that Ashenbrenner and Sons had to send out for more chairs from the church across the street.

When the visitation was over and everybody had gone home, Manny Ashenbrenner turned off all the lights except for one floor lamp at the foot of Cora Sue’s casket; he always left that one lamp burning overnight whenever he had a body lying in state to keep the place from being so lonely. He left to go home just as the clock was striking eleven.

With everyone gone and the place shut down for the night, it couldn’t have been quieter if it had been on the surface of the moon. It was an almost other-worldly quiet. If a feather had been floating through the air, you would have heard it land on the thick gray carpet. If a mouse had walked across the floor, you would have heard its tiny footfalls.

Some slight sound—was it the wind?—caused Cora Sue to open her eyes. She thought she was in her bed at home and was waking up from a dream. She was aware that she had been surrounded by a lot of people earlier, but she thought they were only dream people and hadn’t been bothered by them. She was just glad when they finally went away with their waggling tongues and hot breath and left her alone.

Her bed seemed awfully narrow and unfamiliar; when she tried to move her hips from side to side, she couldn’t. With some difficulty she pulled herself to a sitting position. When she looked around in the dim light, she knew she wasn’t in her own home, in her own bed, but in a place that was unknown but oddly familiar. She expected her mother or father to be there when she woke up, but there was no one; she was all alone.

Oddly enough, she could smell flowers, chrysanthemums especially. She had always liked chrysanthemums but ever since she was a small child she had associated the smell of them with trips to the funeral home when they went to visit somebody who had died. This gave the flowers a significance that the other flowers, however lovely, didn’t possess. She reached over and took a huge chrysanthemum bloom between her hands and inhaled deeply of its scent. Smiling and feeling happy, she extricated her legs and planted her feet on the floor.

She didn’t feel quite herself—no doubt from being in that cramped little bed—but after she had stood upright for a few seconds and took a few steps, she felt fine again. She walked backwards and forwards in a straight line, heel to toe, when she noticed all the chairs but no people. She thought she must be at the bus station or the library or the medical clinic after they had closed down for the night; nothing felt lonelier. She didn’t want to be the only person in such a place after everybody else has left.

She looked around for a pay phone to call her mother to come and get her, but, even if there had been a phone, she wouldn’t have been able to use it because she didn’t have any money. All she could think to do was walk home on her own, no matter how far it was.

She went outside to the street in front of the building and stopped and looked both ways. To her left was darkness but to the right were lights far off in the distance, so she began walking in that direction. Lights meant people and people meant being able to ask for directions. She would get a taxi to take her home and ask the cab man to wait while she went inside to get some money from her mother. She pictured her mother sitting alone on the couch in her pink chenille bathrobe, waiting for her to come home and relieved to see her. She would be happy to pay the cab man.

Everything she saw was strange to her yet oddly familiar. She didn’t know where she was but she had the feeling of having been there before. Objects—buildings, trees, streetlights, cars—existed just outside her field of vision, but when she looked directly at them they seemed to become something other than what they had been. A house became a tree; a telephone pole became a white cat with black spots; a car with people in it became a cloud of dust. She passed a house with a yellow porch light and apple trees in the yard that she was certain she had passed a few minutes earlier. Or did she? If she was simply going around in circles, she hadn’t been aware of turning any corners. Wherever she was, the ordinary rules of things remaining true to themselves didn’t seem to apply.

After a period of walking—had it been hours or only minutes?—she came to a part of town that she was sure she had never seen before except maybe in a dream. There were bars and cafes, bright lights and lively music; people enjoying themselves everywhere—talking, laughing, standing around in bunches. In a doorway a tall man in a uniform was kissing a woman, both of them apparently oblivious to what was going on around them. A monkey dressed as a policeman walked past, rolling its eyes and tootling a horn. Across the street a boy danced while an identical boy accompanied him on an accordion. A small group of onlookers tossed coins, which the accordion player then picked up. A roman candle shot up into the sky and everybody stopped what they were doing and watched it. When it reaches its apex, it exploded with a pop into a ball of golden fire.

She passed a movie theatre with a crowd of people under the marquee waiting to get inside, a crowded penny arcade aglow with yellow light, a dancehall from which music was piped to the street, a liquor store that sold foreign and domestic beers, wines, liquors. She came to a little stand where an old man was selling ice cream cones. He gave her a kind smile, which emboldened her to ask for directions.

“I live on Cherry Street,” she said. “Can you tell me where that is from here?”

“Haven’t ever heard of no Cherry Street, girlie,” he said.

“I’ve lived in this town my whole life and I’ve never seen this part of it.”

“You don’t tell me.”

“Do you know if there’s a telephone around here where I can call my mother to come and get me?”

“You might try the all-night drug store, but last I head their phone was busted,” he said. “Here, have a cone. It’ll make you feel better.” He extended a cone with two dips of chocolate, which, as good as it looked, she didn’t want to take.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “I don’t have any money with me.”

“That’s okay. You can pay me the next time around.”

She knew the opportunity of ever seeing him again was highly unlikely, but she took the cone anyway and continued on her way, eating it. The old man might not have known where Cherry Street was, but he was right about one thing: eating the two-dip chocolate ice cream cone made her feel quite a lot better.

She came to a hotel that had its doors opened invitingly to the street so she went inside. The lobby was cool and hushed like a museum or a library. She went to the sign-in desk and asked the clerk if there was a telephone she might use.

“Pay phones over there,” he said, pointing.

“I don’t have any change,” she said. “Isn’t there any other phone I could use?”

He looked at her and sighed and reached behind the counter and placed a phone on the desk in front of her. “Don’t let the manager see you.”

She dialed the number that she knew so well and when she heard the phone ringing she felt a wave of relief. At last she would hear her mother’s voice and everything would be all right again. After a few rings, though, she heard a recorded voice telling her: Your call could not be completed as dialed. She dialed the number three more times and the same thing happened every time.

“You couldn’t get through to your party?” the clerk asked, watching her the whole time.

“Line’s busy,” she said.

She left the hotel and continued on her way, feeling a little hopeless. She didn’t know what time it was but it seemed late and she wanted to get home and go to bed. Before she went to bed, though, she would have a ham sandwich and a Coke and a couple of chocolate chip cookies at the table in the kitchen while her mother paced the floor in a cloud of cigarette smoke and lectured her about staying out late on a school night. Or—wait a minute—was it a school night? Was she even still in school? She seemed to remember something about finishing school for good and not having to ever go back again. Oh, she was confused all right. How could a person not know if she was still in school or not? She was thinking that maybe she had been hypnotized the way they do in the movies, or that somebody had given her a drug in a drink that she didn’t know about. When she did get home, she would have a lot to tell her parents. Her mother would want to take her right to the doctor to make sure she was all right.

Passing a pet store, closed for the night, she saw a bunch of blue-gray puppies asleep in the window and stopped to get a better look. There were six puppies in all; they couldn’t have been more than a few weeks old. They were so perfect and so artfully grouped together that they might have not have been real except every now and then one of them moved its head or its paw slightly. They seemed close enough that she could touch them except for the glass that stood between her and them. She was hoping that one of them would open its eyes and look at her, when she felt someone standing behind her.

“You’re thinking about Smoky, aren’t you?” a man’s voice said.

She jumped a little, startled, and just stopped short of letting out a little yelp. She always did hate having somebody sneak up on her. “What was that you said?” she asked, turning around and getting a good look at him.

He was older than her but not by much. She thought she had never seen him before but she couldn’t be sure of anything. She realized she should probably be afraid of a man she had never seen before approaching her on the street, but she wasn’t. You can’t always assume that strangers are going to do you harm.

“I said they remind you of Smoky,” he said.

“I was just thinking I’d like to take one of them home with me but I wouldn’t know which one to take. I would want them all.”

“Greedy girl,” he said.

She gave him a little smile and continued on her way. She was a little surprised when he began walking in step beside her.

“You seem kind of lost,” he said.

“I’m not sure if that’s the right word. I woke up in a strange place hours ago—or maybe days ago—and I’ve been trying to find my way home. Everything I see seems kind of familiar but not so familiar, if you know what I mean. I’ve lived in this town my entire life and I’ve never seen this part of it before tonight.”

“Come along with me and I’ll buy you a something to eat,” he said.

“I don’t know if I should.”

“It’s all right, believe me. There’s nothing to worry about.”

He took her to a little restaurant called Afterlife. They sat at a table for two with a white tablecloth and linen napkins. They had a fish dinner with wine served by a mustached waiter in a white apron. It all seemed very fancy to her.

“I never knew this place was here,” she said.

“It’s an out-of-the-way place.”

“It’s funny,” she said. “I don’t know your name.”

“You can call me Boris if you must call me anything.”

“I never knew anybody named Boris before.”

“I didn’t say it’s my name. I said it’s what you can call me.”

“You’re a strange kind of person.”

“You have to get used to things being different now.”

“Why? What do you mean?”

“You’ll have to find out on your own. If I were to tell you, you wouldn’t believe me.”

“I know my family is worried about me. I wish I could call them.”

“You don’t need to worry about them. They know where you are.”

“I feel like I’m having one of those dreams that lasts all night long. You’re somebody that I know I met a while back but I can’t remember your name or much about you. For some reason, you’re in my dream. You’re not real and neither is any of this.”

“You’re giving me a headache,” he said.

“What was that you said about Smoky when you first came up behind me?”

“I said those young pups in the window made you think of Smoky.”

“How is it that you know about Smoky? Who are you, really?”

“I’ve already told you. I’m Boris.”

“That’s not who you are. That’s just a silly name you made up.”

“Smoky was a dog your family had when you were little. He was really old. When you came home from school one day in third grade, Smoky was gone. Your father told you he had gone to heaven, and someday if you were a good person you would see him again.”

“A stranger wouldn’t know that.”

“Did your mother ever tell you you had a brother?”

“I don’t have a brother.”

“You had a brother. He died when he was three weeks old from a heart defect. That was four years before you were born.”

“I don’t believe it. My mother would have told me.”

“Some people are harder to convince than others. Your mother didn’t tell you because she didn’t want to ever talk about it. It was her right to keep it to herself, wasn’t it?”

“I suppose so, but she never kept anything else to herself. What was my brother’s name?”

“If you don’t eat your fish, they’re going to take it back to the kitchen and give it to somebody else.”

When they left the restaurant, he took her to yet another part of her home town she had never seen before. They passed buildings, cars, and people, all of which were something of a blur to her. They ended up walking a long way in the dark. When she flagged, he took her by the hand and pulled her along. She was getting awfully tired but she didn’t complain.

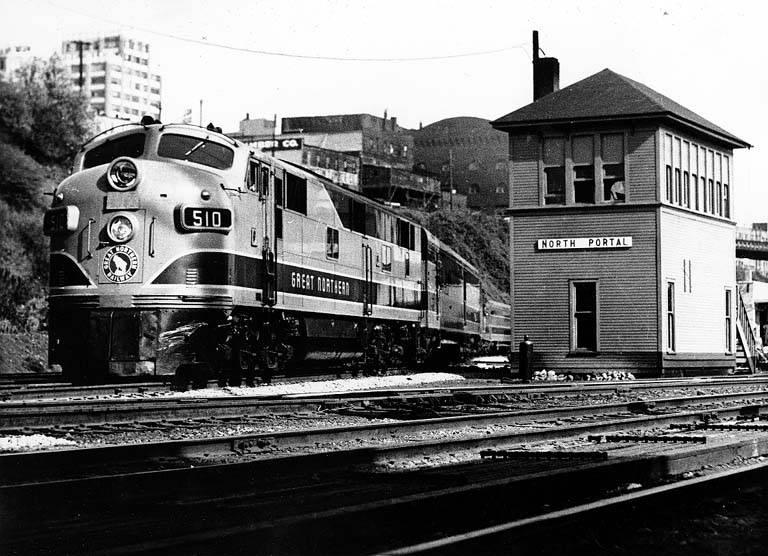

He took her to a train station where, it seemed, the train was ready to pull out. People were everywhere, some waiting to get on the train and others seeing passengers off. She was happy she was with him because he seemed to know where he was going, while she didn’t have a clue. He took her to a certain car on the train and put her in a window seat and sat down beside her.

“Not everybody goes by train,” he said. “Some go by boat, or plane, or car—some even by hot-air balloon. It’s just a matter of where you’re leaving from.”

“Will it be a short trip?” she asked. “I need to be getting home.”

He laughed and picked up a magazine from the back of the seat in front of him and began turning the pages. In a minute the train started to move, slowly at first and then faster. She settled back in the seat and closed her eyes. She would sleep for a while. When she woke up, she would know then where she was going.