Resurrectionist men very rarely attempt to disinter the guests at Burial Day Cemetery. However, every now and again a brave graverobber is found mucking about our lawn, but never has one been successful at accomplishing their task.

The practice of grave robbing or body snatching is perhaps as old as the practice of human burial. Accounts of removing a corpse from its grave for the purpose of dissection, anatomical research or for theft of artifacts buried on or with the person continue to be reported to this day.

In Great Britain and Scotland medical schools were once supplied with cadavers by their local governments, and these local governments obtained these corpses through execution – as they were the bodies of executed criminals and of these there were quite a lot. In 1688, there were only 50 offenses that were punishable by death, but by the end of the 1700’s that number grew to 220. So, what were once considered lesser crimes, such as mild battery or some acts of petty thievery, were now punishable by death. However, by 1823 the Judgment of Death Act lessened what crimes garnered the death penalty. This is very important friends. Think about it, the government gave medical schools the bodies of criminals to use to train future doctors. The supply of these bodies rose drastically when mild crimes sent hundreds and hundreds of people to the gallows, but after the Bloody Code was repealed only a handful of bodies were available, as less people were being executed. The demand of bodies by medical schools increased with their expansions, but with so few available bodies for training something had to be done and fast.

In enters the Resurrectionist.

Body snatching became so prevalent an activity because not only was the crime just a misdemeanor, and so the punishment was merely a fine, but the activity was lucrative as medical schools and doctors paid handsomely. Now, with refrigeration nonexistent at the time bodies decomposed quickly, which meant that there was a constant stream of demand for cadavers. Body snatching became so feared that measures were taken by families to ensure their loved ones were not snatched, from waiting long after the burial at a family members grave to ensure no graverobber removed their loved one, to the use of iron coffins and iron bars to keep graverobbers from stealing freshly dug dead.

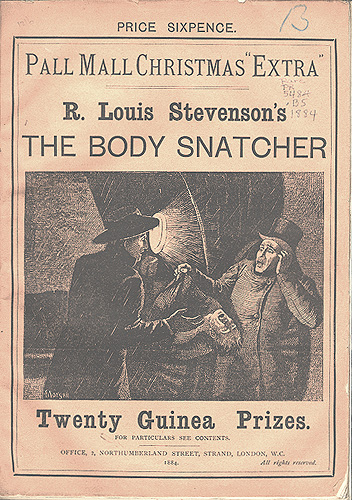

One of the most famous fictional accounts of body snatching is Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1884 short story The Body Snatcher, based on the accounts of some of the most popular resurrectionist men in history, William Burke and William Hare who were employed by Doctor Robert Knox. The Burke and Hare murders occurred from 1827 to 1828 in and around Scotland. Stevenson’s short story begins with the meeting of two former resurrectionist men and takes the reader through their grim history of supplying their college with bodies, the suspicion of murderous deeds, and concludes with what is either a mental break or the universes revenge. You read to decide.

A recent and wondrous novel, Rotters, by Daniel Krause modernizers the tale of the graverobber, setting the story in the United States as a coming of age about a teenage boy who discovers an underground network of resurrectionist men who can trace their history to the murders and scandal of 1800s Scotland. Both stories should surely be read.

There is much, much, much more to say about the history of grave digging and grave robbing and there will be more time to discuss further soon.

Until then, we leave you with a bit of dialogue from two of the most famous literary gravediggers in history, the gravediggers from Shakespeare’s Hamlet Act V , Scene i.

First Gravedigger

What is he that builds stronger than either the

mason, the shipwright, or the carpenter?

Second Gravedigger

The gallows-maker; for that frame outlives a

thousand tenants.

To read Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Body Snatcher for free go here.

To learn more about Daniel Krause’s Rotters go here.

-Gravedigger